Intensive care nurse perspectives on family centred rounds in adult critical care units

Felicia Varacalli, NP, MScN, RN, Gina Pittman, NP, PhD, and Jody Ralph, PhD, RN

By Felicia Varacalli, NP, MScN, RN, Gina Pittman, NP, PhD, and Jody Ralph, PhD, RN

Abstract

Background: Family-centred rounds (FCR) are a component of family involvement in critical care settings. Nurses’ active participation is vital in implementing FCR. However, there is currently

a lack of rigorous literature exploring nursing perspectives of FCR in adult critical care areas.

Purpose: This study explored nursing perspectives of FCR in six adult critical care units across four Southwestern Ontario hospitals.

Methods: A 56-question survey was distributed to critical care nurses working at six adult critical care units through an online Qualtrics® link. Nurses did not need to have experience participating in FCR to participate in this study.

Results: Seventy percent of nurses (n = 135) were overall supportive of FCR. Nurses reported that processes, such as unit culture toward FCR, may impact how well nurses are able to incorporate families into FCR. The most significant advantage of FCR noted was the healthcare team could update family on the patient’s condition. However, they reported time was a major structural barrier to FCR, and the overall greatest barrier noted was the inconsistent or unknown timing of rounds. Tests of association revealed that nurses’ overall supportiveness of FCR was statistically significantly related to their ethnicity (p = .01) and hospital site (p = <.001).

Conclusion: Most nurses are supportive of FCR overall. This research highlights their perceptions of the structures and processes that support them while implementing FCR and factors that may affect their support. It may contribute to developing evidence-based best practices for a higher-quality, standardized, family-centred rounding process.

Keywords: family-centred nursing, clinical rounds, critical care nursing, intensive care units

Implications for Nursing Practice

- Healthcare practitioners working within adult critical care units should work toward formal implementation of family- centred rounds, as most nurses support this practice and felt that family members benefit and quality of care increases from family-centred rounds.

- Developing a standardized structure for family-centred rounds, such as pre-emptively deciding what topics to discuss during rounds and providing an opportunity for families to ask questions after rounds, may increase nursing support for family-centred rounds and help providers manage their time better.

- Supporting nurses through adequate staffing and additional support to reduce workload is imperative to provide sufficient time for nurses to involve families in family-centred rounds.

Background and Purpose

Healthcare practitioners working in critical care provide care for patients who have, or are at risk for sustained disease or injury (Canadian Medical Association, 2019). Many patients in critical care settings cannot speak for themselves for various reasons, leaving families to assume the lead role in voicing the patient’s wishes in care planning and decision-making (Wong et al., 2020). Bedside rounds are a daily practice in which the interprofessional team meets to review clinical information about the patient and formulate a clinical impression to make decisions regarding the patient’s treatments and plan of care (Au et al., 2017). FCR are similar to bedside rounds. However, they include the presence and participation of the family during rounds (Sisterhen et al., 2007). Family presence and participation allow families to contribute to the care planning process and clinical decision-making regarding their loved one’s treatment plan (Au et al., 2017). This important opportunity to participate in rounds reinforces collaboration between the family and the healthcare team and contributes to positive patient outcomes (Heydari et al., 2020).

Considering nurses have an essential role in the execution of FCR, a thorough review of the current literature was performed following consultation from a university librarian. Some studies suggest that nurses are open and welcoming to FCR, while others disagree with this practice (Allen et al., 2017; Santiago et al., 2014; Schiller & Anderson, 2003). Some nurses report that FCR offers better communication with the family (Allen et al., 2017; Roze des Ordons et al., 2020), which can lead to a better understanding of the plan of care for that patient (Allen et al., 2017; Stelson et al., 2016). However, some nurses felt that FCR leads to a longer duration of rounds (Au et al., 2017; Santiago et al., 2014). They also felt there is less discussion and honesty about poor patient prognoses and sensitive information when the family is present (Au et al., 2017; Roze des Ordons et al., 2020; Santiago et al., 2014; Stelson et al., 2016). Less-experienced nurses are more positive toward FCR (Schiller & Anderson, 2003). Nurses support that first-degree biological relatives or the primary contact person for the patient should be invited to rounds, and they were comfortable with up to two family members present (Au et al., 2017). Most nurses believe that the role of the family during FCR is to listen, share patient information and ask questions, and some nurses thought they should participate in decision-making (Au et al., 2017). At the end of rounds, nurses find it helpful to provide a summary to the family

using nonmedical terminology (Roze des Ordons et al., 2020).

There is not an abundance of literature that explores nursing perspectives of FCR in adult critical care areas, and Kydonaki et al. (2021) noted that the present research lacks rigour. In their recent integrative review, Kydonaki et al. (2021) discovered that available current research only comes from Canada or the United States and is of moderate to poor quality. Nurses can significantly influence how well FCR practices are implemented (Kleinpell et al., 2019; Thirsk et al., 2021). Although any healthcare provider can invite the family to join FCR, nurses are the providers who most often communicate with the family, so their engagement can either enhance or hinder family participation in FCR (Doucette et al., 2019). Therefore, this study explored nursing perspectives of FCR in six adult critical care units across four Southwestern Ontario hospitals. The specific research questions in this study were as follows:

- What are nurses’ perspectives of the structures (e.g., staff-to-patient ratios, location of rounds) that support best practices for FCR?

- What are nurses’ perspectives of the processes (e.g., unit culture of FCR, degree of family participation) that support best practices for FCR?

- What do nurses perceive as the greatest advantages to implementing FCR?

- What do nurses perceive as the greatest barriers to implementing FCR?

- Is there a relationship between nurse-related factors (e.g., age, gender, years of experience) and nurses’ overall supportiveness of FCR?

The Donabedian Framework was used to guide this study, and it focused on three concepts – structure, process, and outcome – that work together to assess the quality of care (Donabedian, 1988). This research focused on how the concepts of structure, process and outcome related to FCR in adult critical care settings. Some of the structure variables in this study included the staff-to- patient ratios, duration of rounds, patient acuity, and number of family members present. Some of the process variables in this study included the patterns of invitations to join rounds, family comprehension of the patient’s conditions and treatments, unit culture/attitudes toward FCR, nurse-family relationships, and nursing workload. The outcome variable examined in this study was nurses’ overall supportiveness for implementing FCR in adult critical care units. This research explored the structure and process variables in more depth to contribute to the overall knowledge about best practices for FCR.

Methods and Procedures

The cross-sectional design of this research was mainly descriptive, although tests of association were used to determine which nurse-related factors were associated with nurses’ overall supportiveness of FCR. The Consensus-Based Checklist for Reporting of Survey Studies was utilized (Sharma et al., 2021). A 56-question survey was used to gather data. The survey was adapted from Au et al. (2017), Hetland et al. (2017) and Hetland et al. (2018) with permission granted from both corresponding authors. Adjustments to these surveys included rephrasing questions to improve flow and expanding the demographics section. Questions were also added, based on the literature review, to address the research questions better (Allen et al., 2017; Cody et al., 2018; Kydonaki et al., 2021; Rasheed et al., 2021; Roze des Ordons et al., 2020; Santiago et al., 2014; Stelson et al., 2016). Face validity for the adjusted survey was assessed by three current critical care nurses who did not participate in data collection. A combination of Likert scale, multiple-choice, select-all-that-apply and open-ended questions were used to gather data within the survey. Open-ended questions in this study were limited to the demographic section of the survey to gather information such as age and gender. See Appendix A for the survey.

This study occurred in four urban Southwestern Ontario hospitals, including five adult intensive care units (ICUs), consisting of Level Two and Level Three ICUs, and one adult cardiac care unit. Critical care units range from four to 20 beds in capacity. To de-identify hospital sites, critical care units were randomly labelled as hospital sites one through six for analysis. To our knowledge, these sites do not formally and consistently use FCR at the time of data collection. Some sites had previously implemented FCR, but this practice dissipated once the COVID-19 pandemic began and had not been fully reimplemented. Therefore, we could not capture a site with formal and consistent use of FCR for this study. The inclusion criteria for this study were critical care registered nurses (RNs) currently

working in one of the study sites, entitled to practise with no restrictions with the College of Nurses of Ontario, and able to understand English. This research explored nursing perspectives of FCR; therefore, nurses did not need to have experience participating in FCR to participate in this study. Nurses with post-graduate critical care preparation but not currently working in an adult critical care unit were excluded.

Ethical clearance and oversight were provided by a local university research ethics board and the hospital research ethics boards (REB# 22-177; REB# 23-457; REB# 30JAN2023). Data were collected between February and April 2023 using convenience sampling. The survey was accessed through an online link utilizing the university’s Qualtrics® platform. The survey link was distributed to eligible participants through their institutional email addresses by a designated manager for each hospital. There was one initial recruitment email with two subsequent reminder emails, each sent two weeks apart, within a study period of six weeks per hospital site. Flyers were also posted on the eligible units with a QR code that participants could scan to access the survey. Participants were given the option to receive a $15 gift card as compensation for participating in the study. To restrict participants to one entry per person, participants were required to enter their institutional

email address to claim their gift card.

A consent form was provided to each participant at the beginning of the survey. The survey was anonymous, but demographic information, including age, gender, ethnicity, and hospital site, was optional to mitigate the risk of triangulation. Data are reported in

aggregate format to protect the identity of participants.

IBM Statistical Package for the Social Sciences Version 28 was used to organize and analyze the data and a statistician was consulted. Data analysis took place in two phases. First, all study variables were analyzed using descriptive statistics, including frequencies and percentages for categorical variables, and means, standard deviation, and minimum/maximum values for continuous variables. The analysis ended with descriptive

results for the first four research questions. Next, data from the final research question underwent a series of bivariate analyses to test for association. Bivariate tests (chi-square, Fisher’s Exact, independent samples t-test, Mann-Whitney U) were used to determine if nurse-related factors were associated with nurses’ overall supportiveness of FCR. There was only one significant bivariate result, which was then entered into a binary logistic

regression model, and association and odds ratios were formulated. Parametric testing was used when all test assumptions were met. In cases where test assumptions were not met, nonparametric testing was used.

Data were screened for missing data. The percentage of missing data from each category was less than 5%, and data analysis proceeded for all questions using a completed case analysis (Jakobsen et al., 2017). The missing data were missing completely at random (Mack et al., 2018).

For the final research question, the independent nurse-related factors that were studied included age, number of years as an RN, number of years in critical care, experience with FCR, gender, ethnicity, hospital site, highest level of education, if they took a family nursing course in school, if they felt their education prepared them for FCR, and if they had any intention to leave their current critical care position within six months. Some categorical

questions had small responses within certain groups, so they were combined or eliminated for data analysis.

The dependent variable that determined nurses’ overall supportiveness of FCR was created to be a dichotomous supportive/ unsupportive variable by combining three survey questions that assessed nurses’ perspectives of whether family members should be provided with the option of joining critical care rounds, if they were comfortable having family members present during critical care rounds, and if they believed FCR should be implemented in their institution. The internal consistency of these three questions was measured by determining Cronbach’s Alpha (α = 0.78).

A posthoc power analysis, using the Power and Precision software program, indicated that a sample size of 88 study participants was needed. Therefore, the study sample of 135 participants provided sufficient statistical power for the analyses.

Results

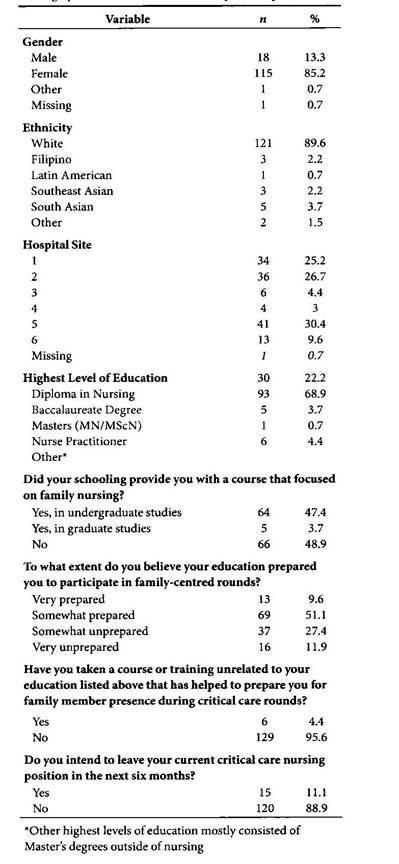

There were 303 RNs who were eligible to participate, and 135 participants fully completed the survey, resulting in a 45% response rate. Some hospital sites had low response rates, so they were combined based on similarities in their ICU level designation, the population size of the area it served, and geographical location. For data analysis, hospital sites 1, 2 and 3 were combined, and hospital sites 4 and 6 were combined. Table 1 presents the descriptive analysis of categorical study variables, consisting of demographic data used as independent variables in the bivariate analysis. Most of the sample identified as female (n = 115, 85.2%), white (n = 121, 89.6%) and had a baccalaureate degree as their highest level of education (n = 93, 68.9%). The overall age, gender and ethnicity of the sample were relatively similar to the Canadian nursing population (Canadian Nurses Association, 2021; College of Nurses of Ontario, 2022; Premji & Etowa, 2014).

Table 1

Demographic and Other Characteristics of the Sample (n = 135)

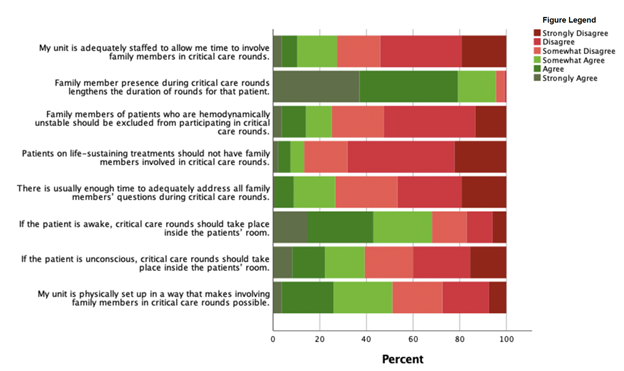

Figure 1 demonstrates nursing perspectives of structures that support best practices for FCR. Of 135 participants, 80% (n = 108) felt that asking questions at the end of rounds was most appropriate. The majority (n = 122, 90.4%) of participants felt that the patient’s age does not affect their decision to invite the family to critical care rounds. More than half of nurses (64.4%; n = 87) felt the patient’s acuity does not affect their decision to invite family members to critical care rounds. Of those who did think the patient’s acuity affected their decision, 33.3% (n = 45) thought that family should have increased presence for higher acuity patients.

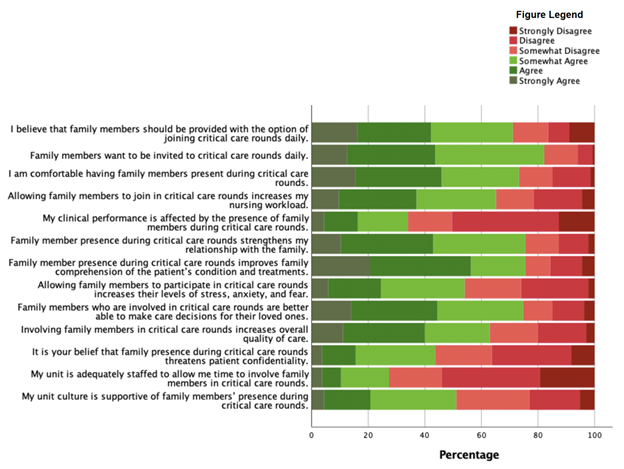

Figure 2 demonstrates nursing perspectives of some processes that support best practices for FCR.

Figure 1

Likert Scale Structure Questions

Figure 2

Likert Scale Process Questions

Regarding the role of the family during critical care rounds, participants endorsed listening (n = 126), sharing information about the patient (n = 97), participating in decision-making

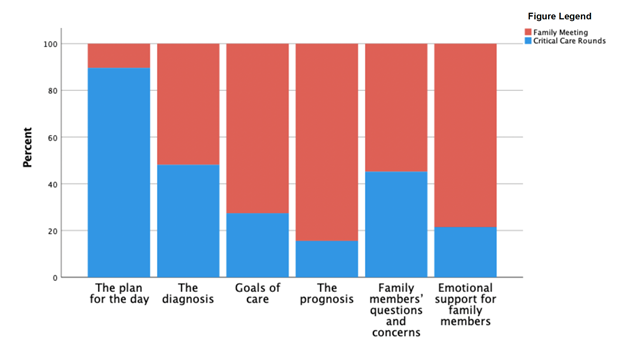

(n = 86), asking questions (n = 93), and advocating for the patient (n = 93). Participants reported they incorporate family into critical care rounds by providing a “lay person” summary during or after rounds (n = 82) and introducing the family to the healthcare team (n = 77). Most nurses felt that FCR decrease the frequency (72.6%; n = 98) and duration (66.7%; n = 90) of formal family meetings. See Figure 3 for what participants identified as the most appropriate setting for discussing specific topics with families.

The top three items found to be valuable about FCR were: the critical care team can update the family on the patient’s condition (n = 100), the family can share valuable information about the patient (n = 84), and there is the opportunity to build a rapport

with the family (n = 70). The top three items found to be barriers to FCR were: inconsistent and/or unknown timing of rounds (n= 95), family’s baseline health literacy (n = 91), and extensive use of medical jargon within the healthcare team (n = 70).

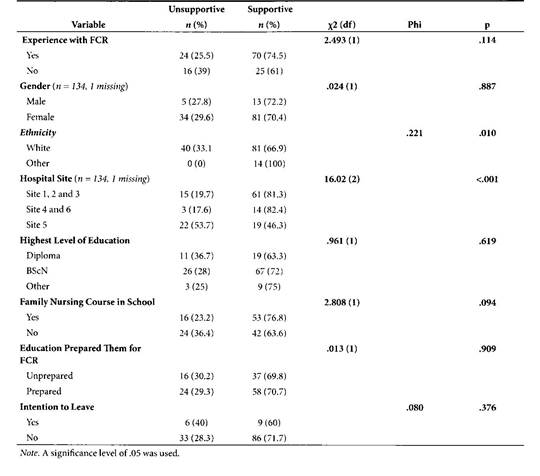

Overall, 71.1% (n = 96) of participants felt that families should be provided with the option of joining rounds daily, 73.3% (n = 99) of participants felt comfortable having family members present during critical care rounds, and 59.3% (n = 80) reported that FCR should be implemented in their institution. Participants who were considered to be overall supportive of FCR (e.g., they agreed with at least two of the above questions) included 70.4% (n = 95) of the total. Table 2 outlines the analyses completed to determine if there

was a relationship between nurse-related factors and nurses’ overall supportiveness of FCR.

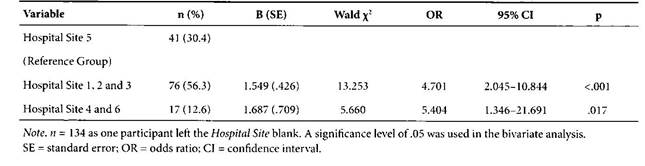

A significant association was noted between ethnicity and supportiveness (p = .01, Phi = .221). Participants in the other ethnicity category are more supportive of FCR than those in the white category. One cell had a count of zero (other, unsupportive), so further statistical testing could not be conducted on this variable. Additionally, supportiveness was significantly related to the hospital sites (χ2(2) = 16.02, p = <.001). A binary logistic regression model was then used to analyze the hospital sites and supportiveness further, as shown in Table 3. The binary regression model used hospital site 5 as the reference group. The overall model was significant (χ2(2) = 15.406, p = <.001). Data were categorized

correctly 72.4% of the time. The model demonstrates that participants from hospital sites 1, 2, and 3 are 4.7 (95% CI =2.045–10.844, B = 1.549, SE = .426, Wald χ2 = 13.253, p <.001)

times more likely to be supportive of FCR compared to those from hospital site 5, and participants from hospital sites 4 and 6 are 5.4 (95% CI = 1.346–21.691, B = 1.687, SE = .709, Wald χ2 = 5.660, p = .017) times more likely to be supportive of FCR compared

to those from hospital site 5.

There was no association between age and supportiveness (p = .412), or between number of years as an RN and supportiveness (p = .301). Participants’ number of years in critical care was not significantly different between those who were supportive (mean rank = 64.82) or unsupportive (mean rank = 73.80), U = 145, z = -1.229, p = .219.

Figure 3

Nurses’ Perspectives of Topics to Discuss in Critical Care Rounds vs Family Meetings

Table 2

Nurse-Related Factors, by Supportive Status (n = 135)

Table 3

Supportiveness, by Hospital Site (n = 134)

Discussion

Structures of FCR

The results demonstrate that most nurses in this study are supportive of FCR overall. However, nurses identified that time was a major structural barrier. Most nurses in this study noted that their unit was not sufficiently staffed to allow them the time to involve the family in rounds (72.6%), family involvement in rounds lengthened rounding time (95.6%), and that time limited their ability to address all family members’ questions during rounds (73.3%). Adequate staffing in critical care units is not a newly identified concern in nursing (Thirsk et al., 2021). However, supporting patient care through adequate nursing staffing can assist them in involving families in critical care rounds, as it reduces nurses’ workload, and the literature demonstrates that this is true for other family-centred care (FCC) initiatives (Hetland et al., 2017; Thirsk et al., 2021). Nurses participating in studies by Santiago et al. (2014) and Au et al. (2017) also expressed that FCR lengthens rounding. Although longer rounding times may be beneficial for the patient and family, Hetland et al. (2017) found that inadequate time affected nurses’ willingness to involve families in FCC initiatives. Additional support for nurses is needed to allow them the time to involve families in FCR. Developing a standardized structure for FCR may help manage rounding time for nurses, other interdisciplinary staff, and families, so that all parties have an expected timeline in mind. Most nurses in this study (80%) believe that taking questions from family members at the end of FCR is best, and this practice was well received by healthcare practitioners and families in Au et al. (2017), as well. Having dedicated time to

ask questions at the end of rounds is a structural factor that could be considered when implementing FCR.

Processes of FCR

Most nurses in this study believe involving families in FCR can help them understand patients’ conditions and treatments (76%) and allow them to make better care decisions for their loved ones (75%). Conversely, Au et al. (2017) found that some nurses had reservations about FCR because they felt that it confused families more than it improved their understanding. However, Heydari et al. (2020) found that families who help make decisions in their loved one’s care felt more empowered, increasing their perceived

quality of care. In the current study, most nurses (63%) felt that the overall quality of care increases when families are present during FCR, which suggests support for this process.

Nurses in this study felt that listening was the primary role for families during FCR. However, they ascribed other roles to families, such as sharing information about the patient, participating in decision-making, asking questions, and advocating for the

patient during FCR, and this was supported in the published literature, as well (Roze des Ordons et al., 2020; Stelson et al., 2016). Another study reported that families also may consider themselves as passive listeners, reinforcing this perceived role (Au et al., 2017). Although listening is important, Au et al. (2017) suggested that role clarification is needed and should be implemented when introducing families to FCR, as nurses ascribed more roles to families than families perceived for themselves.

Nurses in this study were almost evenly divided on whether they felt that FCR increased stress, anxiety, and fear in families, and the literature also shows this divide (Au et al., 2017). The increase in knowledge gained from attending FCR may help families to understand the patient’s condition better; however, nurses worry that this increased information might inflict fear or stress on families. In a literature review by Al-Mutair et al.

(2013), families of patients in critical care reported that receiving information is one of their most important needs, and they felt this need is often unmet. Families felt that when nurses participated in FCC initiatives, it actually reduced their stress and anxiety (Doucette et al., 2019). Most nurses felt that there is decreased discussion of unfavourable information during FCR, and this seems to be unanimous across much of the present literature (Au et al., 2017; Roze des Ordons et al., 2020; Santiago et al., 2014; Stelson et al., 2016). Future research should investigate if the decreased discussion of unfavourable information is related to the feelings of stress, worry or anxiety that nurses felt they were exerting on families. It may also be beneficial for practitioners to preemptively decide what topics to discuss during FCR, as critical care units could gain increased support to implement FCR from nurses with this practice.

The nurses in this study had divided opinions on whether they felt their unit culture supported implementing FCR. This division could be detrimental to implementing FCR, as the support of the unit, including managers, directors, interdisciplinary staff, and other nurses, is crucial to successful implementation. A positive unit culture has been found to support nurses in implementing various FCC initiatives (Kleinpell et al., 2019; Thirsk et al., 2021). Factors that can influence a unit’s culture include the nursing culture specifically, resistance to change, lack of support from upper management, and a lack of organizational resources, such as short staffing or high nurse-to- patient ratios (Heydari et al., 2020; Kleinpell et al., 2019).

Advantages and Barriers to FCR

To the authors’ knowledge, literature that investigates nurses’ perception of the greatest advantages and barriers to FCR is limited to one study (Roze des Ordons et al., 2020). The top advantage that nurses in this study identified was that the critical care team can update the family on the patient’s condition. Regardless of FCR implementation status, families usually want frequent updates on the patient, especially if their status is changing (Wong et al., 2020). Having this daily access to information is found to be beneficial for both nurses and families (Roze des Ordons et al., 2020). The most prevalent barrier nurses in this study identified was the inconsistency or unknown timing of rounds. Healthcare providers have identified that family members can be frustrated with this unpredictability (Roze des Ordons et al., 2020), and families themselves have expressed frustration with this, as well (Cody et al., 2018; Roze des Ordons et al., 2020; Stelson et al., 2016). This barrier may be difficult to overcome depending on the other responsibilities of the physician aside from rounding. Increasing the amount of physician coverage, dispersion of

responsibilities, and having a dedicated window for rounding may be helpful to develop more consistent rounding times.

Nurses’ Supportiveness of FCR and Nurse-Related Factors

Nurse-related factors were compared to nurses’ overall support toward FCR. Ethnicity was significantly related to supportiveness toward FCR, with a more positive perspective coming from ethnicities other than white. The participants in this study mainly identify as white (89.6%). However, Canadian RNs are disproportionately white (Jefferies et al., 2019), and only about 15% of all Canadians in the nursing profession belong to a visible minority (Premji & Etowa, 2014). Visible minority RNs in Canada are under-represented in advanced practice or specialty nursing areas (Premji & Etowa, 2014). However, there is little to no difference in the knowledge or skills used between white and visible minority RNs (Cruz & Sawchuk, 2021). To our knowledge, no articles compared the ethnicity of RNs to their

overall perspective of FCR in adult critical care units. However, Quindemil et al. (2013) note that many non-Western cultures attest to collectivism rather than the individualistic approach undertaken by most Western cultures. Many non-Western cultures do not view the patient as an autonomous entity, but rather as part of a family network (Quindemil et al., 2013). This may provide some explanation as to why non-white ethnicities in this

study are more supportive of FCR. However, more insight could be obtained through a qualitative lens. Future research could also investigate which non-white ethnicities are the most supportive, as non-white ethnicities were combined for statistical analysis

due to their limited representation.

There was a significant relationship between which hospital site nurses worked at and their overall supportiveness of FCR. The nurses employed at hospital sites 1, 2, 3, 4 and 6 were more supportive of FCR than those at hospital site 5. Interestingly, hospital site 5 had a very high response rate (82%) compared to the other hospital sites. This finding could indicate that different hospital sites may support FCC initiatives better, including FCR, in their daily practice. Hospital support could include utilizing on-site educators or offering continuing education to their staff. At an organizational level, they could have differing levels of access to resources that promote FCR, such as higher staffing levels, decreased nursing workloads, decreased patient acuity, and a more supportive unit culture. They may also have more support staff, which could decrease nursing workload. This study did not gather site-specific data regarding the organizational and unit structures. It is, therefore,

unclear what is causing this discrepancy between institutions, although this could indicate that inconsistencies in nursing support of FCR across the published literature may be institutionally dependent (Allen et al., 2017; Au et al., 2017; Stelson et al., 2016).

Many factors in this study did not reveal significant associations. However, the results are still worth acknowledging and interpreting beyond statistical significance. The study sampled nurses who had and did not have experience participating in FCR and compared their support toward FCR. There was no significant difference in the overall supportiveness between these two groups. To our knowledge, previous research has examined only the perspectives of nurses with FCR experience. This result demonstrates that after experiencing FCR, perspectives do not significantly change. Also, the age of participants, years of experience as an RN, and years in critical care all had no significant effect on

nurses’ supportiveness toward FCR. Conversely, previous literature found nurses with less experience to be more positive toward FCR (Santiago et al., 2014; Schiller & Anderson, 2003) and support a more inclusive role for the family during FCR (Au et al., 2017). This finding may suggest that views of FCR are shifting to become more inclusive, regardless of age or experience. Lastly, this study produced nonsignificant results when investigating if

education contributes to nurses’ overall supportiveness of FCR. Hetland et al. (2017) found that those with advanced nursing degrees were more likely to incorporate family into their standard care. Although not significant, there was a trend of increasing supportiveness of FCR with increasing levels of education from those nurses with a Diploma (63.3% supportive), a baccalaureate degree (72% supportive) and other degrees, including master’s and nurse practitioner designation (75% supportive).

Limitations

A limitation of this study is that it focused on nursing perspectives of FCR, so there were some participants who had never experienced FCR who participated in this study. This lack of experience may have impacted their perspectives of FCR. Also, the sample only represents Southwestern Ontario. Therefore, results may not be generalizable to the rest of Canada or other countries. Additionally, the sample in this study predominantly identified as female and white, and even though it may be representative of the population, it is difficult to generalize findings to the minority groups.

The survey tool has limitations, as it underwent limited reliability and validity testing. This was due to the survey design being mainly descriptive. A Cronbach’s alpha was determined when creating the supportiveness variable, and face validity was obtained by three different critical care RNs regarding the overall survey.

Conclusion

This study highlighted nursing perspectives of FCR in six adult critical care units across four Southwestern Ontario hospitals. Most critical care nurses in this study were overall supportive of FCR. Nurses reported that a lack of time was identified as a large structural barrier. Supporting nurses through structural resources, such as adequate staffing and a standardized structure of rounds, may be beneficial. Nurses felt that families who participated in FCR could make better care decisions, and the overall quality of care increased. Processes, such as the perception of increased family stress and anxiety, may impact nurses’ willingness to incorporate families into FCR. Developing a standardized

structure for family-centred rounds, such as preemptively deciding what topics to discuss during rounds and providing an opportunity for families to ask questions after rounds, may help increase nursing support for FCR and help providers manage their time better. Nurses noted that the greatest advantage of FCR was that the healthcare team could update the family on the patient’s condition, and the greatest barrier was the inconsistent or unknown timing of rounds. Finally, it highlighted that participants’ ethnicity and the hospital site where they are employed are statistically significantly associated with their overall supportiveness of FCR. Future research should investigate factors that may contribute to these significant results. This research helped to fill the knowledge gap regarding nursing perspectives of FCR in adult critical care units. It will help future researchers develop

evidence-based best practices for a higher quality, standardized, family-centred process for patient care rounds.

Author notes

Felicia Varacalli, NP, MScN, RN, University of Windsor, Windsor, ON.

Gina Pittman, NP, PhD Assistant Professor, Faculty of Nursing, University of Windsor, Windsor, ON.

Jody Ralph, PhD, RN, Associate Professor, Faculty of Nursing, University of Windsor, Windsor, ON.

Corresponding author: Felicia Varacalli, NP, MScN, RN, University of Windsor, Windsor, ON. Email: varacalf@uwindsor.ca

Acknowledgments

Thank you to Dr. Debbie Sheppard-Lemoine and Dr. Lindsey Jaber from the University of Windsor for reviewing this research as part of the thesis committee. Also, thank you to William Bannon for assisting with the statistics embedded in this research.

Funding and Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that there is no funding and no conflict of interest to declare.

References – Add link to PDF

Appendix A – Add link to PDF

(002).png)